The forecast shows lighter wind, we hope it will not die down completely in us. 137nm to go.

2020

03

Dec

2020

03

Dec

Provisioning from Trahiti

The fast ride goes on. Still no fish, but we’re indulging in luxury food from Tahiti: for lunch we had a salad with ham (for Christian), with feta cheese (for me) and with ham and feta (without stupid green bits) for Leeloo ![]()

220 nm to go!

2020

02

Dec

The miles are ticking down

With 15 knots of wind from the East and steady conditions we are rushing along with 6 to 7 knots. The water temperature has already dropped from 29.1° C to 28.3°. 269 miles to go!

2020

01

Dec

Towards the Austral Islands

We are just motoring out of the pass S of Marina Taina–there’s not a breeze to be felt, but according to the forecast it’s blowing 15 knots out there. We just have to get away from the high mountains of Tahiti to find it… 390 nm to go to Raivavae!

2020

29

Nov

Dirty Tahiti

The propaganda war against cruisers goes on in Tahiti. We saw in a magazine (Tahiti Pacifique) that after a horrible accident where a cruiser kid was killed by a speeding motorboat right next to his parents’ boat, not speeding in lagoons is critizised, but again the sailboats are blamed for ‘blocking channels’ and posing a risk?! The big anchorage off Marina Taina is (yet again) scheduled to be ‘cleared of boats’ and according to a pamphlet by the harbour master of Papeete anchoring will soon be forbidden (or already is) everywhere in Tahiti. Cruisers get blamed for polluting, damaging coral and loitering in the lagoon.

Last week we had heavy rainfalls and Pitufa was floating in debris that had been swept into the lagoon: plastic bottles, plastic bags, flip-flops, cans, but also a flatscreen (who would have thought they’d float?), tyres, a motorcycle helmet (no driver attached, we checked) and the sea smelt like a sewer from all the overflown cess pools. It’s so much easier to point at cruisers (who don’t have a lobby) instead of admitting and tackling the serious problems Tahiti has…

2020

29

Nov

Hot and humid

We arrived a week ago in Tahiti and went into super-busy mode immediately. Not on our to-do list (we have tons of projects with the things we ordered from the US), but with unexpected chores: We spent two days repairing the sail, one day repairing the kerosene stove, 2 days repairing our new(!) dinghy as the damn thing arrived with serious damage from the transport, then we got duty-free diesel, did some doctor’s appointments (I had a loose filling replaced and my retinas checked after a serious fright–I saw flashes, something that looked like a tear through my vision–turns out it was a visual migraine…), shopping, lots and lots of internet chores, etc. and now we’re eager to head South towards the cooler Austral Islands. It looks like we’ll get a weather window on Tuesday ![]()

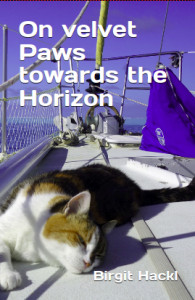

It’s getting seriously hot and humid here in Tahiti (rainy season is getting into full swing) and our aging ship’s cat doesn’t cope well with the heat (she loses her appetite, throws up, gets grumpy), so we’ll cool her down in the Austral islands to keep her fresh for bit longer ![]()

2020

25

Nov

Gluten-free cruising

Ever since Christian had some health problems 5 years ago we’ve been cooking and baking gluten-free. In the beginning that was quite a challenge: I googled recipes and dismissed most because we couldn’t get the ingredients for them out here. I experimented a lot and found a few basic rules for gluten-free flour:

- corn starch (available in minimarkets around the world) makes doughs hard and stable

- rice flour (available in bigger supermarkets) makes things crispy (ideal for batters, flatbread, pizzas)

- tapioca flour (available in basically all minimarkets in the Pacific area) makes doughs gooey and glues things together (great in crepes)

- buckwheat flour (available only in Tahiti in the French Poly area) lets doughs rise (ideal for bread)

- almond flour (available only in Tahiti in the Fr. Poly area) is great for quiche and pie bottoms

We stock up on luxury items like gluten-free cake mixes, lasagna sheets, spaghetti, etc. and of course lots and lots of buckwheat flour whenever we are in Tahiti. In remoter areas there’s a wide variety of local veg to cook gluten-free meals:

Breadfruit, maniok, iams, sweet potatoes and taro are great in traditional (ask locals!) preparations, but also in fusion-food style dishes (breadfruit lasagna, gnocchi made from breadfruit dough, taro gratin, sweet potato goulash–there are no limits for creative cooking!)

2020

25

Nov

Miss Pfaff

We managed to get several metres of heavy-duty dacron material (some from a sailmaker after all others had refused to sell any, some from fellow cruisers–thanks!), got the sail down, stuffed it into the saloon and set to work. The photo’s not quite realistic, we didn’t have a third person to take the pic so you can’t see how Christian had to hold up the sail with one hand, hold down the foot of the sewing machine with the other and occasionally help along the motor with his third hand… Our sewing machine Miss Pfaff (a Pfaff 92 from the 70s) courageously worked her way through more layers of sailcloth than we would have thought possible: we needed an awl, a sailing needle and gloves to penetrate the material in order to knot the loose ends…

After two working days the sail’s ready to be hoisted again, but there’s no weather window in sight…

2020

24

Nov

New Photos!

Remnants of Untouched Nature in the Tuamotus

Here are some impressions from our quest for wildlife and wilderness in the Tuamotus. A few specks survived the ever expanding, destructive copra industry and unsustainable exploitation. We document, report, and try to raise awareness.

(58 photos)

2020

23

Nov

10 Fun Ways To Flood A Bilge…

Birgit Hackl, Christian Feldbauer: 10 Fun Ways To Flood A Bilge, All At Sea Caribbean, November 2020, p. 38–42. Download the whole magazine for free or read the online version of this article.

Birgit Hackl, Christian Feldbauer: 10 Fun Ways To Flood A Bilge, All At Sea Caribbean, November 2020, p. 38–42. Download the whole magazine for free or read the online version of this article.

2020

19

Nov

Back again in Tahiti

We arrived in Tahiti last night after the breeze had died down–we had to motor the last few miles. It looks like we may get a weather window for the Austral Islands next week, so we’ll try to get all our chores done quickly before that. I have to visit my dentist, we have to repair our foresail and of course we’ll think of a few bits and pieces that we have to buy in Papeete, but we’ll try to get away as quickly as possible again.

2020

18

Nov

Gennaker

This morning the wind dropped to 5 to 9 knots and Pitufa was stumbling along goose-winged. We got out the gennaker–it took us about an hour until we had everything sorted out, quite a cumbersome procedure. Now Pitufa’s flying along under that huge blue-yellow lightwind sail and it’s so calm that Leeloo came up to check whether we’re already at anchor. Pitufa’s companionway ladder is 6 feet high and almost vertical–quite a climb for a 20 year old cat ![]()

66 nm to go!

2020

18

Nov

Almost like at anchor

We’re having a slow, but comfy ride. A bit rolly sometimes, but mostly like being at anchor. I’ve written two articles in two days and now I’m working on a ‘through the tuamotus’ gallery for our blog. Christian’s proof-reading my book and programming. Very different from our recent trips (climbing along walls, extreme cooking with ballistic ingredients, but mostly seasickish lying around, trying to hold on to the sofa ![]() ). 140 nm to go!

). 140 nm to go!

2020

17

Nov

Comfy sailing

We’re having a smooth down-wind sail in light winds. We’re not doing much more than 4 knots, but it’s really comfy. Just now we’re passing through a little squall, it’s sunny despite the downpour and we’re sailing through a rainbow gate ![]() 175 nm to go!

175 nm to go!

2020

16

Nov

Underway to Tahiti

Cruiser’s plans are always written in the sand and the weather as well as outer circumstances dictate our itineraries. We set out from Tahanea this morning planning to sail straight down to Tubuai (Austral Islands). When we rolled out the foresail we saw that the leech line had ripped open the top half of the sail–sailing close-hauled the sail wouldn’t have its proper shape and we would cause further damage. We have therefore changed course and are headed for Tahiti. I’ll see a dentist there (a loose filling needs attention), we’ll get out the sewing machine and repair the sail and then we’ll be hopefully soon be able to continue to the Australs. We won’t go ashore more than necessary–Covid numbers are soaring in Papeete. 255 nm to go!